How to Build an Online Learning Community: 6 Theses

This presentation was offered as a virtual keynote at the University Innovation Alliance Spring 2020 Convening. All text from the slides is included below.

Educational institutions are spaces for learning, but more specifically, they are spaces for social learning. And so our role as educators and administrators of educational institutions has to be focused on building community in addition to offering courses, designing curriculum, and credentialing.

“There is consensus in the literature about the benefits of a student’s sense of belonging. Researchers suggest that higher levels of belonging lead to increases in GPA, academic achievement, and motivation.” – Carey Borkoski, “Cultivating Belonging”

There is no one-size-fits-all set of best practices for building a learning community, whether on-ground or online. We have to start by looking to our own existing communities for expertise. Who at our institutions is already doing this work and doing it well? And who has figured out how to do it effectively online? How can we better support those efforts? And we have to start by finding out who are students are, what they need to be successful, and how our institutional mission does (and sometimes doesn’t) align with our practices.

“Today’s college students are the most overburdened and undersupported in American history. More than one in four have a child, almost three in four are employed, and more than half receive Pell Grants but are left far short of the funds required to pay for college.” – Sara Goldrick-Rab and Jesse Stommel, “Teaching the Students We Have Not the Students We Wish We Had”

“The reason we are talking about basic needs today is because the students brought it to our attention. A student spoke up, ‘the reason I am not succeeding in college is because I haven’t eaten in two days.’ In fact, 1 in 2 of your students are experiencing food insecurity. In the last 30 days.” – Sara Goldrick-Rab, Dream 2019

Some Data About Bias in education from Soraya Chemaly's “All Teachers Should Be Trained to Overcome Their Hidden Biases”:

- Black girls are twelve times more likely than their white counterparts to be suspended.

- While Black children make up less than 20% of preschoolers, they make up more than half of out-of-school suspensions.

- Teachers spend up to two thirds of their time talking to male students; they also are more likely to interrupt girls. When teachers ask questions they direct their gaze towards boys more often, especially when the questions are open-ended (In STEM fields).

62% of higher education faculty/staff stated they’d been bullied or witnessed bullying vs. 37% in the general population. People from minority communities are disproportionately bullied. (Hollis 2012)

51% of college students claimed to have seen another student being bullied by a teacher at least once and 18% claimed to have been bullied themselves by a teacher. (Marraccini 2013)

“We need to design our pedagogical approaches for the students we have, not the students we wish we had. This requires approaches that are responsive, inclusive, adaptive, challenging, and compassionate. And it requires institutions find more creative ways to support teachers and prepare them for the work of teaching. This is not a theoretical exercise — it is a practical one.” – Sara Goldrick-Rab and Jesse Stommel, “Teaching the Students We Have Not the Students We Wish We Had”

“You cannot counter structural inequality with good will. You have to structure equality.” – Cathy N. Davidson

We should begin our efforts toward building community by designing for the students who need that community most, the ones most likely to have been feeling isolated even before the pandemic: disabled students, chronically ill students, students of color, queer students, and students facing housing and food-insecurity.

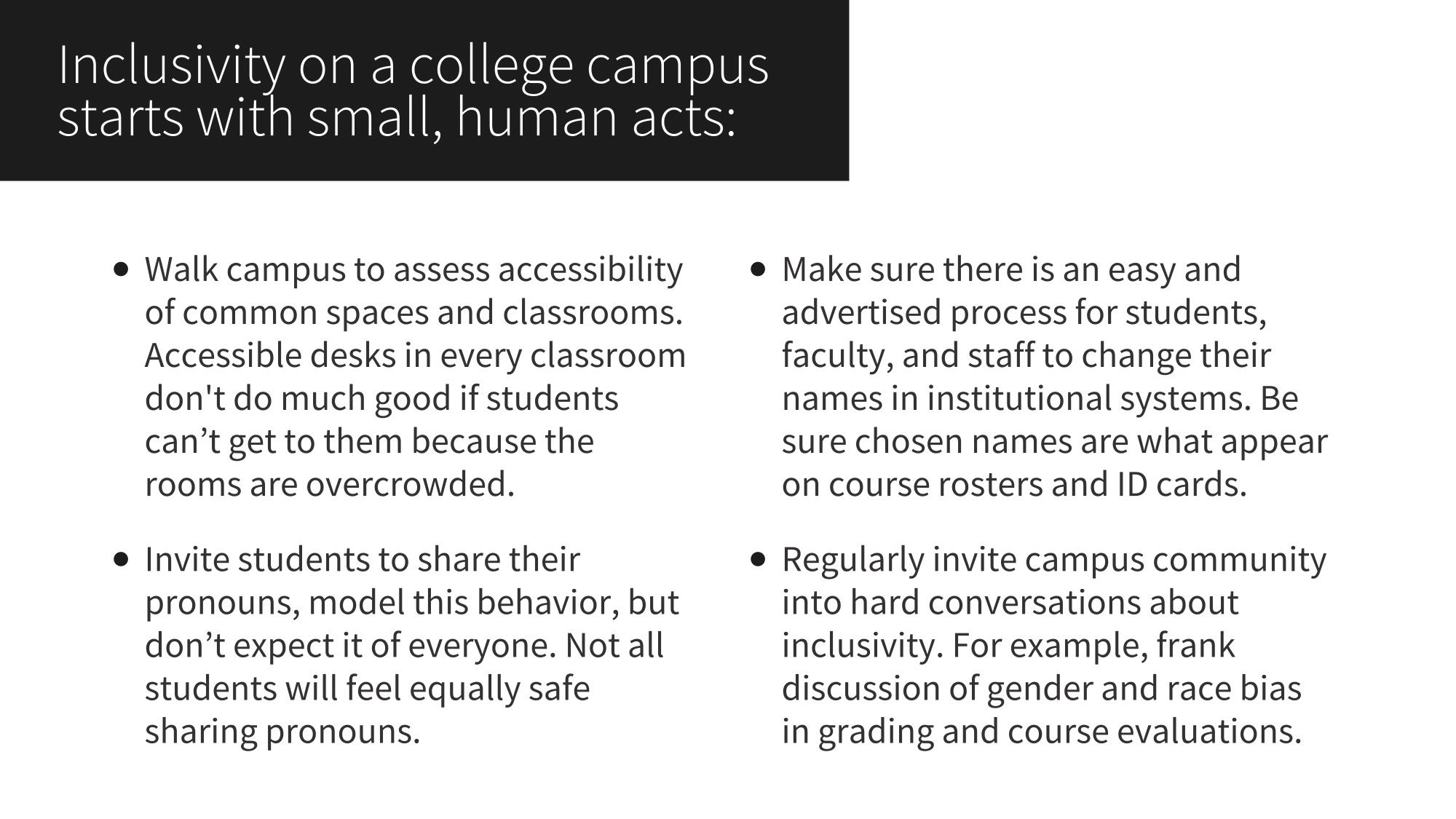

Inclusivity on a college campus starts with small, human acts:

- Walk campus to assess the accessibility of common spaces and classrooms. An accessible desk in every classroom doesn’t do much good if students can’t get to that desk because the rooms are overcrowded.

- Invite students to share their pronouns, model this behavior, but don’t expect it of everyone. Not all students will feel equally safe sharing pronouns.

- Make sure there is an easy and advertised process for students, faculty, and staff to change their names within institutional systems. Make sure chosen names are what appear on course rosters and ID cards.

- Regularly invite the campus community into hard conversations about inclusivity. For example, a frank discussion of race and gender bias in grading and course evaluations.

What does it look like to do this kind of work online? How do we walk our virtual campuses to address accessibility concerns? Where do we hold the necessary town hall meetings to address hard questions about inclusivity?

The first mistake of many online programs is that they try to replicate something we do face-to-face, mapping the traditions of on-ground institutions onto digital space. Imagine the most lively on-ground classroom in full resolution with all its various sights and sounds, then compare that to the restrictive interface of a learning management system.

Over the last several months, I’ve heard lots of talk about how teachers can build community within online courses, but not nearly enough talk about how we build and maintain the larger idiosyncratic culture that is core to an educational institution.

The crucial part of this work is not keeping administrators and faculty connected to students, but about building space for students to stay connected with each other. In his ”Student Guide” to the online “pivot,” Sean Michael Morris writes, “If possible, reach out to other students in your classes and create a support network. Use whatever digital means necessary to stay in touch.”

Educational campuses have libraries, coffee shops, cafeterias, quads, lawns, amphitheaters, stadiums, hallways, student lounges, trees, park benches, and fountains. Ample space for rallies, study-groups, conversation, debate, student clubs, and special events. Few institutions pay much attention to re-creating these spaces online. The work done outside and between classes (which is the glue that holds education together) is attended to nominally if at all. Some learning happens best in rooms with walls, but some learning happens best in fields or in libraries or in town squares.

What we have is a series of online classes with no real infrastructure to support the work students do on college campuses outside and between those classes. Many online programs have the bureaucratic trappings of formal education without the rich ecosystems.

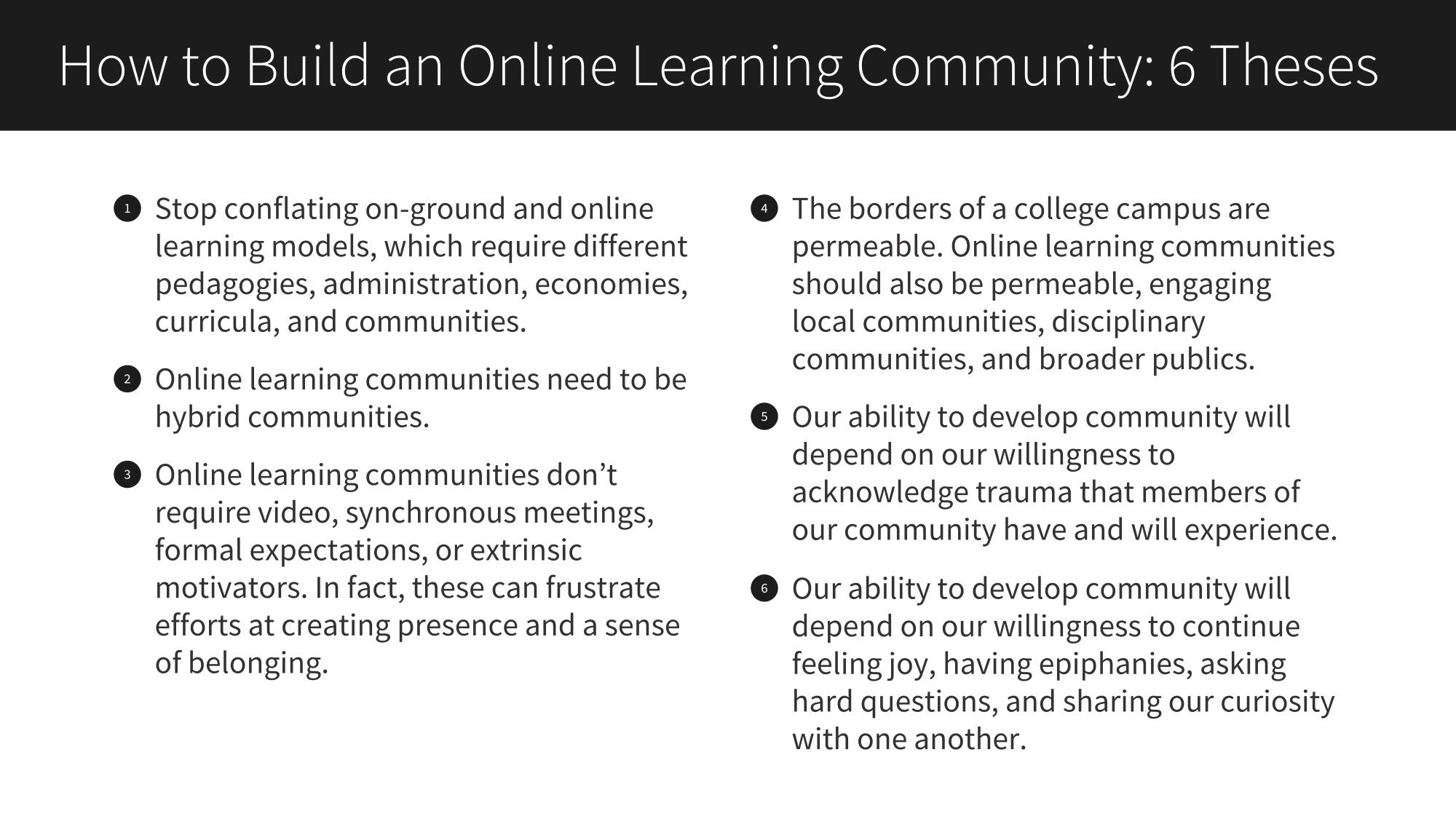

How to Build a Virtual Learning Community: 6 Theses

1. Stop conflating on-ground and online learning models, which require different pedagogies, administration, economies, curricula, and communities.

The key failure of online learning has been its attempt to duplicate, replicate, or simply dump into an LMS the content and strategies of on-ground learning. We need to recognize that online learning uses a different platform, builds community in different ways, demands different pedagogies, has a different economy, functions at different scales, and requires different curricular choices than does on-ground education. Even where the same goal is desired, very different methods must be used to reach that goal.

Supporting innovative digital pedagogies means investing in robust inter- and intra-institutional collaborations, and it means hiring and creating a culture for the development of digital pedagogues.

The rhetoric of a physical classroom — its pedagogical topography — can certainly dictate how we teach within it: where the seats are, which direction they face, whether they’re bolted down, what kind of writing surfaces are on the walls, how many walls have writing surfaces, whether there are windows, doors that lock, etc. The same is true of the virtual classroom: is it password protected, what kind of landing page do we arrive on when we enter the course, how many pages allow interaction, can students easily upload and share content. Each of these predetermined variables allows (and sometimes demands) a certain pedagogy. The physical classroom, though, can usually be rearranged (to some extent) on the fly. Most online learning platforms make customization slow or difficult enough to deter responsiveness or impulsivity.

2. Online learning communities need to be hybrid communities.

Many students face very specific challenges at home: housing insecurity, domestic violence, lack of access to internet or other technology, physical disability, chronic and acute illness. We can’t assume all students (or staff) can simply join our communities from home. We have to build with an understanding of these challenges and, even where learning remains fully (or mostly online), we have to continue to make space on college campuses for students who have no other homes from which to “shelter in place.”

According to the Hope Center’s National #RealCollege Survey, out of 86,000 students surveyed, 56% were housing insecure in the previous year, and 17% were homeless.

LGBTQ young adults had a 120 percent higher risk of reporting homelessness compared to youth who identified as heterosexual and cisgender. (voicesofyouthcount.org)

"Residents living in a university residence hall (this does not include university apartments) must be out of the building by Saturday, December 15, 2018, at 10 a.m., or a charge of $100 per hour will be assessed along with potential conduct sanctions. Unfortunately, no exceptions can be made for you to remain beyond that date and you will not be able to enter the residence halls over the break for any reason. The halls reopen and students may move back in on Thursday, January 17, 2019, at 9 a.m.” – From the University of California Berkeley Housing Policy

3. Online learning communities don’t require video, synchronous meetings, formal expectations, or extrinsic motivators. In fact, these can frustrate efforts at creating presence and a sense of belonging.

Not all students, faculty, and staff will be able to meet synchronously, and different students learn in different ways at different times.

Staring directly into the faces of 20 other people, compelled to engage via video from within their own homes (and sometimes their bedrooms), doesn’t reproduce (or even simulate) the kinds of academic and informal gatherings that happen on a college campus.

In far too much online learning, we over-architecture engagement, reducing it to a series of tasks with point values, rather than leaving enough breathing room for organic and intrinsically-motivated community to develop.

4. The borders of a college campus are permeable. Online learning communities should also be permeable, engaging local communities, disciplinary communities, and broader publics.

“Critical formative cultures are crucial in producing the knowledge, values, social relations and visions that help nurture and sustain the possibility to think critically, engage in political dissent, organize collectively and inhabit public spaces in which alternative and critical theories can be developed.” – Henry Giroux, “Thinking Dangerously: the Role of Higher Education in Authoritarian Times”

5. Our ability to develop community will depend on our willingness to acknowledge trauma that members of our community have and will experience.

"There is robust evidence that social isolation and loneliness significantly increase risk for premature mortality, and the magnitude of the risk exceeds that of many leading health indicators.” – Julianne Holt-Lunstad, et. al. “Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review”

The effects of trauma are even greater for students who are sick or caring for loved ones who are sick. And the symptoms of isolation, loneliness, or acute illness can’t be adequately anticipated by many of our more traditional pedagogies and institutional bureaucracies.

“A Trauma-Informed Approach to Teaching Through Coronavirus” from Teaching Tolerance:

- Establish a routine and maintain clear communication.

- Relationships and wellbeing should take priority over assignments and compliance.

- Actively encourage and support a sense of safety, connectedness, and hope.

- Acknowledge that trauma is not distributed equally. Those struggling before the pandemic will have an even more difficult time now.

“From everything we know about learning, if the trauma is not addressed, accounted for, and built into the course design, we fail. Our students fail.” – Cathy Davidson, “The Single Most Essential Requirement in Designing a Fall Online Course”

Ultimately, we have to care for the well-being of every member of our community. How administrators treat faculty influences how faculty treat staff and students. And all of this is effected by the care (or lack of care) from state government, boards of regents, or regional accrediting bodies.

6. Our ability to develop community will depend on our willingness to continue feeling joy, having epiphanies, asking hard questions, and sharing our curiosity with one another.

“As a classroom community, our capacity to generate excitement is deeply affected by our interest in one another, in hearing one another’s voices, in recognizing one another’s presence.” – bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress

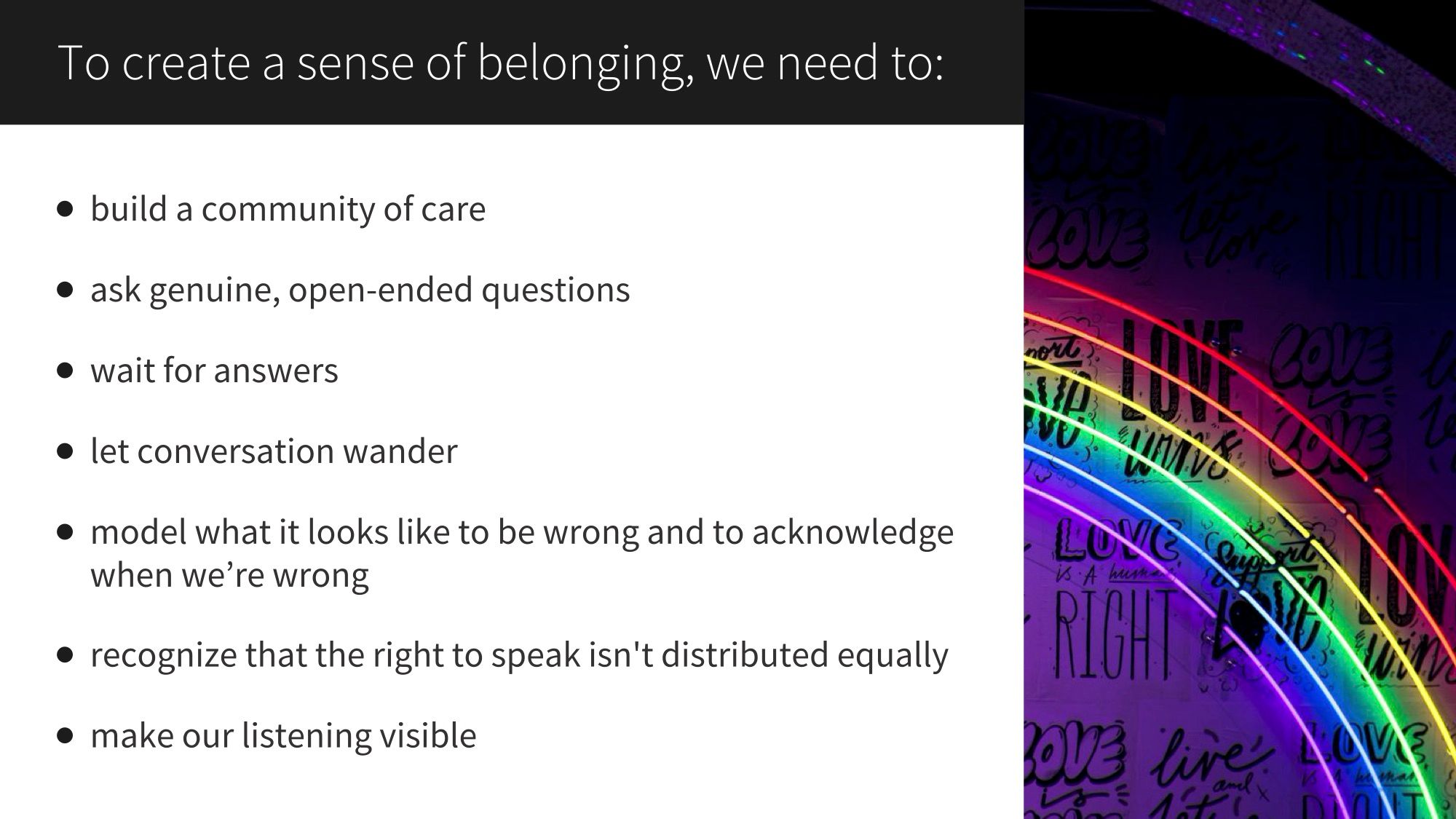

In brief, to create a sense of belonging, we must:

• build a community of care

• ask genuine, open-ended questions

• wait for answers

• let conversation wander

• model what it looks like to be wrong and to acknowledge when we’re wrong

• recognize that the right to speak isn't distributed equally

• make listening visible

Listening looks different online, especially when we engage asynchronously. In a discussion forum, much of our listening becomes invisible. But, even in a videoconferencing tool like Zoom, listening looks different. In an on-ground discussion, we might viscerally feel the hum of a room, listening for intake of breath and watching for people leaning forward at the edge of speech. How do we create adequate space for contribution online? How do we reckon with the fact that silence online can often feel a whole lot more … silent?

“We need more, not fewer, ways to listen for the voices of students reflecting on education. We need more, not fewer, ways to include students in conversations about the future of teaching and learning in college. These conversations cannot begin by sending a signal to students that their voices don’t matter.” – Sara Goldrick-Rab and Jesse Stommel, “Teaching the Students We Have Not the Students We Wish We Had”

Start by trusting students.