Ungrading: an FAQ

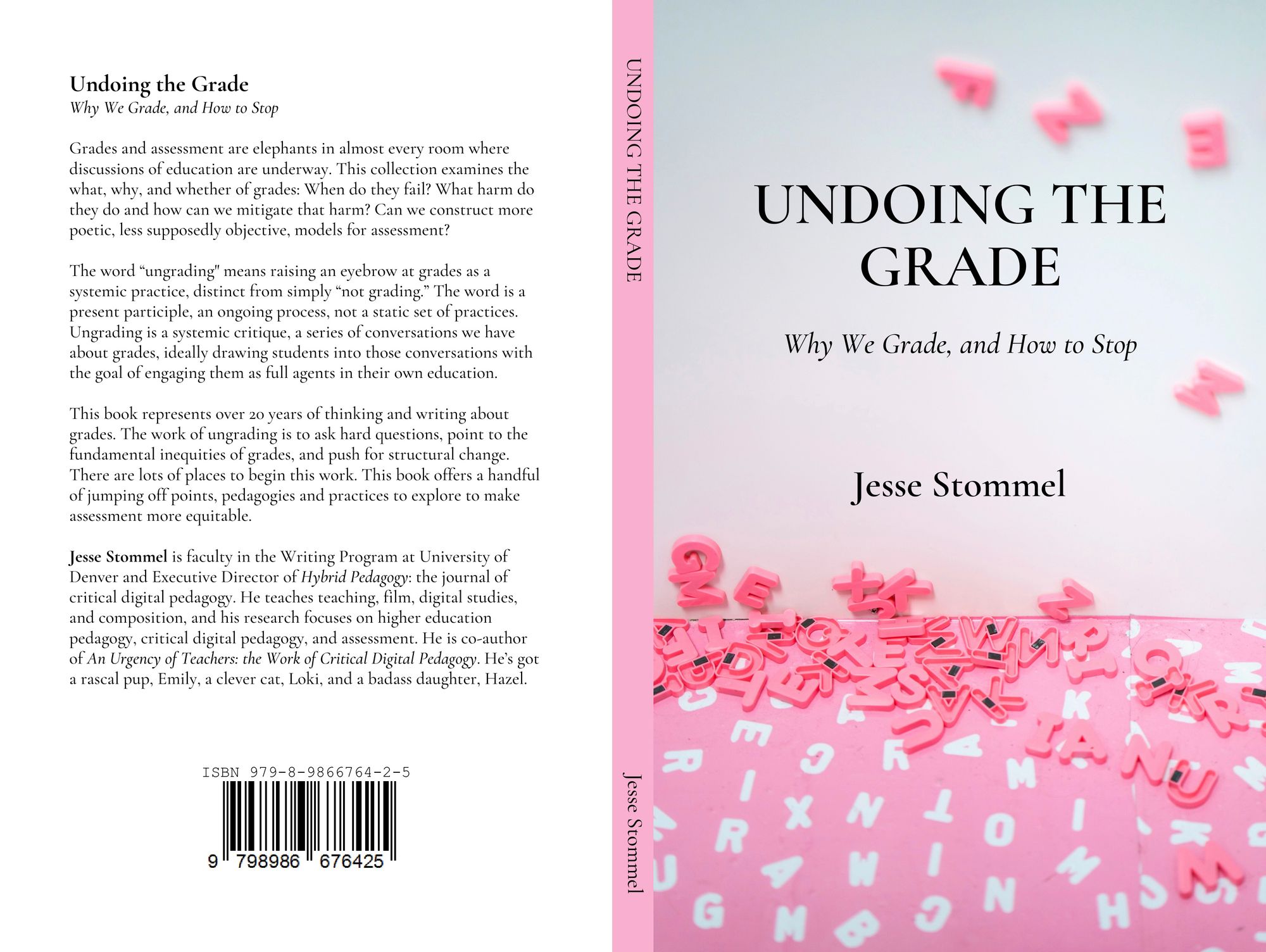

This piece was revised and expanded for my new book, Undoing the Grade: Why We Grade, and How to Stop, available now in paperback and Kindle editions.

When I lead workshops on ungrading and radical assessment, I often start with the question, "why do we grade?" The most common answer from the teachers I work with is, "because we have to." Grades are the bureaucratic ouroboros of education. They are baked into our practices and reinforced by all our (technological and administrative) systems. Teachers continue to grade because so much of education is built around grades.

I'm increasingly struck by the degree to which we approach grades and grading as inevitable. If we can’t “imagine the world as though it might be otherwise,” as Maxine Greene would say, we are stuck with the bizarre customs and habits our institutions have adopted.

I don't grade student work, and I haven't for 20 years. This practice continues to feel like an act of personal, professional, and political resistance. I’m still required to turn in final grades, by all of the institutions where I've worked, so I have students write self-reflections. The bulk of my “grading” time is spent reading these and adapting our course on the fly as I get to know the students. Over the years, I've gotten lots of questions about the what, why, and how of my approach. These are some of those questions and my answers.

Wait, you don't put grades on individual assignments? How do students get As, Bs, or Cs in your class?

My assessment approach centers around self-evaluation and metacognition. I ask students to write process letters about their work, and I ask them to reflect frequently on their own progress and learning. The most authentic assessment approaches, in my view, are ones that engage students directly as experts in their own learning.

I offer feedback with words and sentences and paragraphs, or by just talking to students, rather than using a crude system for quantitative evaluation. I also encourage students to see their peers as a primary audience for their work, rather than just me.

Students in my classes give themselves a grade at the end of the term. I say, “I reserve the right to change grades as appropriate,” but over 20 years, I’ve seen students grade themselves incredibly fairly. The students in my courses get As, Bs, Cs, and even Fs.

Can you share specific examples of the kinds of prompts you use for the self-reflections you have students do?

In an introductory course, like Digital Studies 101 or freshman composition, I begin with more frequent self-reflections and more directive prompts. In advanced courses, I might have students do a midterm self-reflection with directive prompts and an open-ended final self-reflection. I've also experimented with asking students to blog their way through a course, reflecting constantly (but less formally) on their process.

A midterm self-reflection might begin with questions like, "what aspects of the course have been most successful for you so far? What thing that you've learned are you most excited about? What challenges have you encountered?" I usually ask students to quote from or link to examples of their work right within the self-reflection. I don't necessarily respond to every self-reflection (especially in a large class), so one of the last questions invites students to ask for particular kinds of feedback.

A final self-reflection will either include a shorter series of questions that build upon the midterm self-reflection, or it might have a single open-ended prompt, such as: "Write me a short letter that reflects on your work in this class. Consider the work you did on the final project, your work earlier in the term, the feedback you offered your peers on their work, and how you met your own goals. Include links to examples of your work. Did you miss any significant work? Is there anything you are particularly proud of? What letter grade would you give yourself?"

(Feel free to borrow any of the examples here as a jumping off point to hone your own approach).

Why don't you grade?

I wrote a longer piece that answers this question in detail, "Why I Don't Grade." In short, the act of grading does harm to students and causes teachers unnecessary stress. Research shows grades don’t help learning and actually distract from other feedback/assessment. Alfie Kohn writes, "when students from elementary school to college who are led to focus on grades are compared with those who aren’t, the results support three robust conclusions: Grades tend to diminish students’ interest in whatever they’re learning [...]; Grades create a preference for the easiest possible task [...]; Grades tend to reduce the quality of students’ thinking [...]."

Grades frustrate intrinsic motivation. In an educational system that increasingly centers grades and quantifiable outcomes, students work to the grade rather than doing work for the sake of learning. Students ask questions like, "what are you looking for," "how many points is this worth," not "what will I do," but "what should I do, and how will it be graded?"

Taking grades at least partly off the table means I can have a whole different set of conversations with students. With all of us focused on grades, not enough of our work together is tuned toward genuine curiosity or wondering at what we each (tentatively) think about the stuff of the course. In Education for Critical Consciousness, Paulo Freire describes “an education of ‘I wonder,’ instead of merely ‘I do.’” Grades frustrate those conversations.

Learning is not linear, and meaningful learning resists being quantified. Our assessment approaches should create space for learning not arbitrarily delimit it. How, for example, can we “test” whether a student has had an epiphany? What standardized mechanism can account for a student learning experience we (and they) couldn’t have anticipated? How can we evaluate (with a percentile) the significance of a student changing their mind about something? How can a letter grade account for the complexity of failure, struggle, or even success? These kinds of questions call for a pedagogy that is less algorithmic and more human, more subjective, more compassionate. Too often teachers fail to ask students how, where, and when learning happens for them.

Grading is so ingrained in our educational systems that small acts of pedagogical disobedience can't do enough to change the larger (and hostile) culture of grading and assessment. What I hope for is that my courses at least help students (and teachers) see behind the curtain of this system. My goal is not to create a learning environment entirely free of grades and quantitative assessment (which would be futile), but rather to create a safe space for students to ask critical questions about grades, about how school works, and about their own learning.

Have you ever felt pressure from above to grade? If so, how did you overcome this pressure? What if I'm [contingent, precarious, sessional, adjunct]?

The work of teaching is increasingly precarious and the ability of teachers to carve our own paths through the work is under threat. Academic freedom (like the ability to make critical decisions about our teaching practices) must extend to precarious teachers.

Each institution where I've worked has had a different set of rules, structures, and norms. Navigating those hurdles (and institutional cultures) has been a challenge. I've been contingent for most of my teaching career, 11 of 20 years. During that time, I never put grades on student work, but it took me over a decade to start talking as openly as I am here about my approach. Some coping strategies that have worked for me: (1) I make sure my pedagogy is well-researched; (2) I bring students into the conversation about my approach; (3) I figure out what the firm rules are and follow them. We usually internalize way more restrictions than there actually are.

In fact, conventional approaches to grading are usually at direct odds with our institutional missions. So I look to those missions when advocating for teachers to have autonomy in their decisions about how, when, and whether to grade.

I haven’t seen a college mission statement with any of these:

• Pit students and teachers against one another

• Rank students competitively

• Reduce the humanity of students to a single low-resolution standardized metric

• Frustrate learning with approaches that discourage intrinsic motivation

• Reinforce bias against marginalized students

• Fail to trust students’ knowledge of their own learning

Most assessment mechanisms in higher education simply do not assess what we say we value most.

Does ungrading make students anxious?

Students sometimes start from a place of anxiety about the removal of grades (because they’ve been conditioned to see them as markers of success, even if other things actually work better as markers of learning), but that anxiety usually gives way pretty quickly.

The key, I think, is making sure students believe us, that they aren’t worried a rug will be pulled out from under them. This means teachers have to start by cultivating a sense of trust in the classroom. And building trust is hard.

When it comes to talking to students about not grading, I usually follow their lead. If they need the conversation, individually or as a group, we have it. Sometimes, they don’t. As long as I've been teaching, I still tweak my approach every single time. And the approach has to emerge from conversation with students about their specific contexts.

Does ungrading affect the scores students give you on course evaluations?

Generally, I think my pedagogical approach has helped my course evaluations (particularly my emphasis on compassionate and flexible pedagogies).

My scores on course evaluation questions specifically about grading have depended on how well the questions were phrased to allow for my approach. At my current institution, for example, the specific wording is: "The instructor provided clear criteria for grading" and "the instructor returned graded materials within a reasonable amount of time, considering the nature of the assignment." The words "criteria" and "returned graded materials" are out of sync with my approach. Much of the "criteria" in my courses is determined by students, and I neither "grade" materials, nor "return" them in any conventional way. So, it's unsurprising to me that I often score below department and college averages for these questions, even though my scores for all other questions is above department and college averages.

This is a perfect example of how pedagogical decisions can be baked into administrative structures at an institution. This is, in my view, a direct threat to academic freedom. And as we critically examine how we're grading students, we must also take a hard look at institutional assessment mechanisms for courses and instructors. Ultimately the problem is the way course evaluations are designed, not ungrading as an approach. But it's important to acknowledge that, as problematic as they are, course evaluations have a direct impact on the livelihood of teachers, particularly those who are already marginalized or working precariously. So, we can't teach (or talk about teaching) as though course evaluations don't exist.

Do you know if ungrading is sometimes used for STEM courses?

Ungrading seems to work well across disciplines, age groups, and at all levels of education. Certainly, lots of modifications are necessary depending on the specific context.

I know quite a few STEM folks who ungrade in various ways. Some specific stuff I’ve seen work in STEM classes: project-based learning with self-assessment, process notebooks (like a lab notebook but with an emphasis on metacognition), and collaborative exams. Exams, in particular, are at their best when they are formative tools for learning, not just standardized mechanisms for summative (or end-of-learning) assessment. Collaborative exams allow students the opportunities to learn from and teach each other. Open-book and self-graded exams are not as good at sorting or ranking students, but they are often just as good (if not better) tools for learning.

Clarissa Sorensen-Unruh has written quite a bit about her experiments with ungrading in her Chemistry courses. What I find so refreshing about her accounts is how she narrates both the successes and failures on her journey. She writes, "My students, many of whom are from underserved populations (i.e. particularly Latinx and/or Native American), deserve to be included in the discussion of their own grades. I hope by increasing their agency by using ungrading, my students increase their motivation to learn and their mastery of the material."

I teach a class of [50, 100, 400] in a large lecture hall. How can ungrading work in a course like that?

For several years, I taught up to 9 classes each term at as many as 4 institutions. I’ve taught traditional college classes with over 100 students. What I’ve found is that compassion scales. And allowing space for student agency scales.

Teaching metacognition and having students self-evaluate is just as effective (and more necessary) in large classes, where I can't possibly see inside the brain/process of each student. Reading students' self-reflection letters is what helps me "see" student learning and know when they need support or feedback.

A few things that work well when ungrading with large groups:

• Have students read about metacognition and invite open discussion about grading

• Several self-evaluations throughout the term asking students to reflect on their work

• One letter to class offering general feedback, noting trends, and responding to common questions

• Invite students to make individual appointments and reach out to those who are struggling

• Share (with permission) anonymized highlights from self-reflections, including data re: grade distribution, and invite conversation

• Adjust grades as needed but generally give students the grades they give themselves

With a group of 50, 100, or 400, I can’t give the same amount of feedback that I would with a smaller group, so I do more talking and writing to the class as a whole. Ultimately, not grading saves time. It doesn’t mean I do less work. I just put my energy into other work that better supports student learning.

Would you describe ungrading as a [decolonizing, radical, progressive, feminist, critical] pedagogical practice?

Ungrading is a key part of my critical pedagogical approach, but it only works as a radical, decolonizing, feminist practice, if it’s done carefully and alongside other critical pedagogical practices.

Grades reinforce teacher/student hierarchies (and institution/teacher hierarchies) while exacerbating other problematic power relationships. Women, POC, disabled people, neurodiverse people are all ill-served by a destructive culture of grading and assessment.

In removing grades, though, we have to be sure we aren't just shifting the goalposts for students, replacing clear policies with "hidden curriculum." Ungrading can unsettle power dynamics in productive ways, but it can also reinforce structural biases if those biases aren't explicitly acknowledged and accounted for. Toward this end, I share and discuss data about bias in grading with students. I also have a responsibility to spend time actively challenging my biases and reflecting on my own privilege/marginalization. I believe an actively anti-racist, anti-misogynist, anti-ableist approach is more effective than supposedly “objective” approaches like blind grading (which just maintain the status quo, rather than accounting for privilege or marginalization).

The biggest problems arise, in my view, when we devise learning outcomes, determine policies, and craft assessments before we’ve even met the specific students we’re working with. Too many of our approaches treat students like they’re interchangeable and fail to recognize their complexity. Not every student begins at the same place, nor is it even reasonable to imagine every student can, or should, end up at the same place. Ultimately, critical pedagogical practice has to acknowledge the background, context, and embodied experience that both teachers and students bring to the classroom. Any predetermined standardized metric will almost necessarily fail at that.

Different students learn in different ways at different times.

Without grades, how do you motivate students to complete their work? If you aren't grading, but your colleagues are, won't students de-prioritize the work for your classes?

Students do sometimes prioritize other graded courses over mine (although it is much rarer than people are often worried it would be). And I’m okay with that. Honestly, it seems like good time management for students to prioritize work with a hard deadline.

I’m trying to encourage intrinsic motivation, and it’s difficult for that to compete with extrinsic motivators (for me too). But when students clear the decks of other work and turn to work for my classes, they can do so with a gusto. And it is common for students in my classes to work harder for those classes than any others (but in their own time), because they have a reason better than points.

I can push students harder, because I’m not regularly grading them. When we trust each other, we can challenge each other more.

How Should I Start Ungrading?

Ungrading works best when it's part of a more holistic pedagogical practice – when we also rethink due dates, policies, syllabi, and assignments – when we ask students to do work that has intrinsic value and authentic audiences. However, it starts with teachers just talking to students about grades. None of the techniques described here are necessary beyond that one. Demystifying grades (and the culture around them) helps give students a sense of ownership over their own education. There are lots more suggestions on ways to begin in my previous post, "How to Ungrade," but I say start simply with a single conversation with students and let your approach evolve from there.