Ungrading: an Introduction

This piece was revised and expanded for my new book, Undoing the Grade: Why We Grade, and How to Stop, available now in paperback and Kindle editions.

This presentation was offered in collaboration with the Big Questions Institute. A full transcript of the slides is below. And a video of the live presentation is also available.

"Ungrading" means raising an eyebrow at grades as a systemic practice, distinct from simply “not grading.” The word is a present participle, an ongoing process, not a static set of practices.

Pivot /ˈpivət/

: to turn on or as if on a pivot

If your institution just continued grading during the pandemic, “business as usual,” here’s what all those grades were measuring:

- how well students and teachers “pivoted” to online

- whether students had necessary access and support at home

- the ability of students to “perform” in a crisis

What all those grades mostly weren’t measuring: student learning and/or content knowledge.

"Deciding to ungrade has to come from somewhere, has to do more than ring a bell, it has to have pedagogical purpose, and to be part of a larger picture of how and why we teach." ~ Sean Michael Morris, "When We Talk About Grades, We Are Talking About People"

Some foundational questions about assessment:

- Who is assessment for? How does this question force us to rethink how institutions structure their systems for evaluation?

- What's the difference between grading and feedback? To what extent should teachers be readers of student work (as opposed to evaluators)?

- Why do we grade? How does it feel to be graded? What do we want grading to do (or not do) in our classes (for students or teachers)?

- What would happen if we didn’t grade? What would be the benefits? What issues would this raise for students and/or teachers?

“Assessment tends so much to drive and control teaching. Much of what we do in the classroom is determined by the assessment structures we work under.” ~ Peter Elbow, “Ranking, Evaluating, and Liking: Sorting Out Three Forms of Judgment”

Ranking. Metrics. Norming. Objectivity. Uniformity. Accreditation. Measurement. Rubrics. Outcomes. Quality. Data. Performance. Averages. Excellence. Curves. Inflation. Mastery. Standardization. Rigor.

I would argue grading, by any of our conventional academic metrics, undermines the work:

- Grades are not good incentive.

- Grades are not good feedback.

- Grades encourage competitiveness over collaboration.

- Grades are not good markers of learning.

- Grades don't reflect the idiosyncratic, subjective, emotional character of learning.

- Grades aren't “fair.”

Historically, grades are more of an anomaly than anything else. They are very recent technology.

Prior to the late 1700s, performance and feedback systems in Education were incredibly idiosyncratic. The first “official record” of a grading system was from Yale in 1785. Throughout the 19th Century, they became increasingly comparative, numerical, and standardized.

The A-F system appears to have emerged in 1898 (with the “E” not disappearing until the 1930s) and the 100-point or percentage scale became common in the early 1900s. Letter grades were not widely used until the 1940s. Even by 1971, only 67% of primary and secondary schools in the U.S. were using letter grades. (Schinske and Tanner)

An “objective” system for grading was created so systematized schooling could scale. And we’ve designed technological tools in the 20th and 21st Centuries that have allowed us to scale further. Toward standardization and away from subjectivity, human relationships, and care.

The grade takes the complexity of human interaction within a learning environment and makes it machine-readable: [A/A-] [A-/B+] [F+] [97%] [59%] [18/20] [10/20] [high first] [low 2:1]

“Research shows three reliable effects when students are graded: They tend to think less deeply, avoid taking risks, and lose interest in learning itself.” ~ Alfie Kohn, “The Trouble with Rubrics”

In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire argues against the banking model of education, “an act of depositing, in which the students are the depositories and the teacher is the depositor.”

In place of the banking model, Freire advocates for “problem-posing education,” in which a classroom or learning environment becomes a space for asking questions -- a space of cognition not information.

Start by Trusting Students.

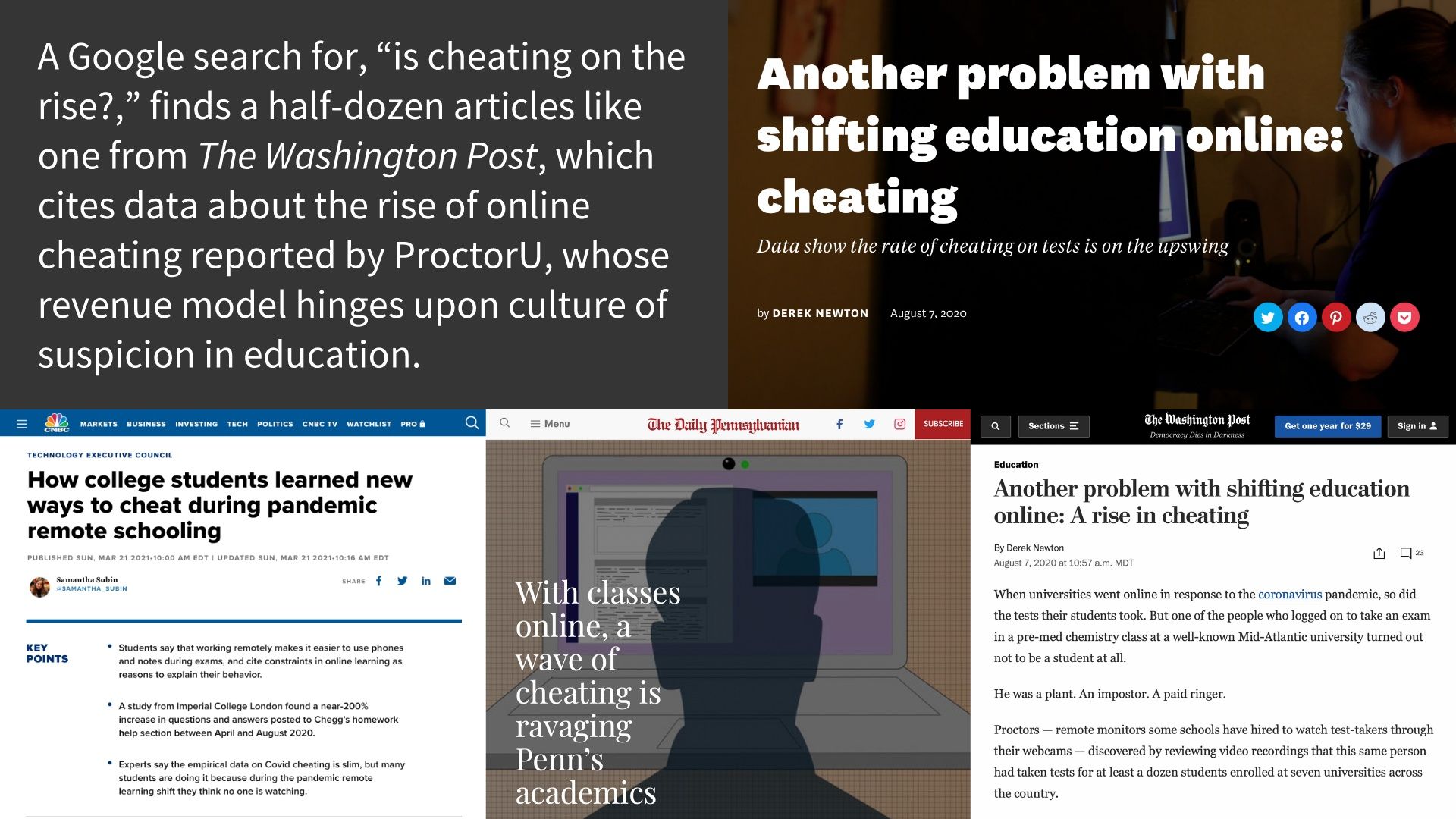

A Google search for, “is cheating on the rise?,” finds a half-dozen articles like one from The Washington Post, which cites data about the rise of online cheating reported by ProctorU, whose revenue model hinges upon culture of suspicion in education.

In 1963, Bowers surveyed roughly 100 institutions and found that “75 percent of the surveyed students admitted to cheating at least once in their college careers. … The numbers have not changed much since then." McCabe, et. al.'s 2012 Cheating in College: Why Students Do It and What Educators Can Do About It includes findings from 150,000 students recently surveyed, showing that "between 60 to 70 percent of respondents admitted cheating." (Lang, Cheating Lessons)

The remote proctoring industry “is expected to grow from being a $4 billion market in 2019 to a nearly $21 billion market in 2023.” (Vox)

Honorlock, one of these proctoring technologies, markets itself by saying, "Our patented online test proctoring software maintains program integrity while providing extensive learner flexibility." Meanwhile, their patented approach to “ensuring integrity” lacks integrity itself, going further than assuming students cheat by actually baiting them into doing it. They have patented the use of honeypot websites, which offer answers to exams, tracking students accessing these pages and giving them incorrect answers.

Conventional grading is often at odds with our institutional missions. So far, I haven't seen a school mission statement with any of these:

- We pit students and teachers against one another

- We rank students in competitive ways

- We measure output with little concern for the learning process

- We value extrinsic over intrinsic motivation

- We start from a place of deep suspicion of students

- We assess in ways that reinforce bias against marginalized students

Data About Bias in Education (as reported by Soraya Chemaly, “All Teachers Should Be Trained to Overcome Their Hidden Biases”):

- Black girls are twelve times more likely than their white counterparts to be suspended.

- While Black children make up less than 20% of preschoolers, they make up more than half of out-of-school suspensions.

- Teachers spend up to two thirds of their time talking to male students; they also are more likely to interrupt girls. When teachers ask questions they direct their gaze towards boys more often, especially when questions are open-ended.

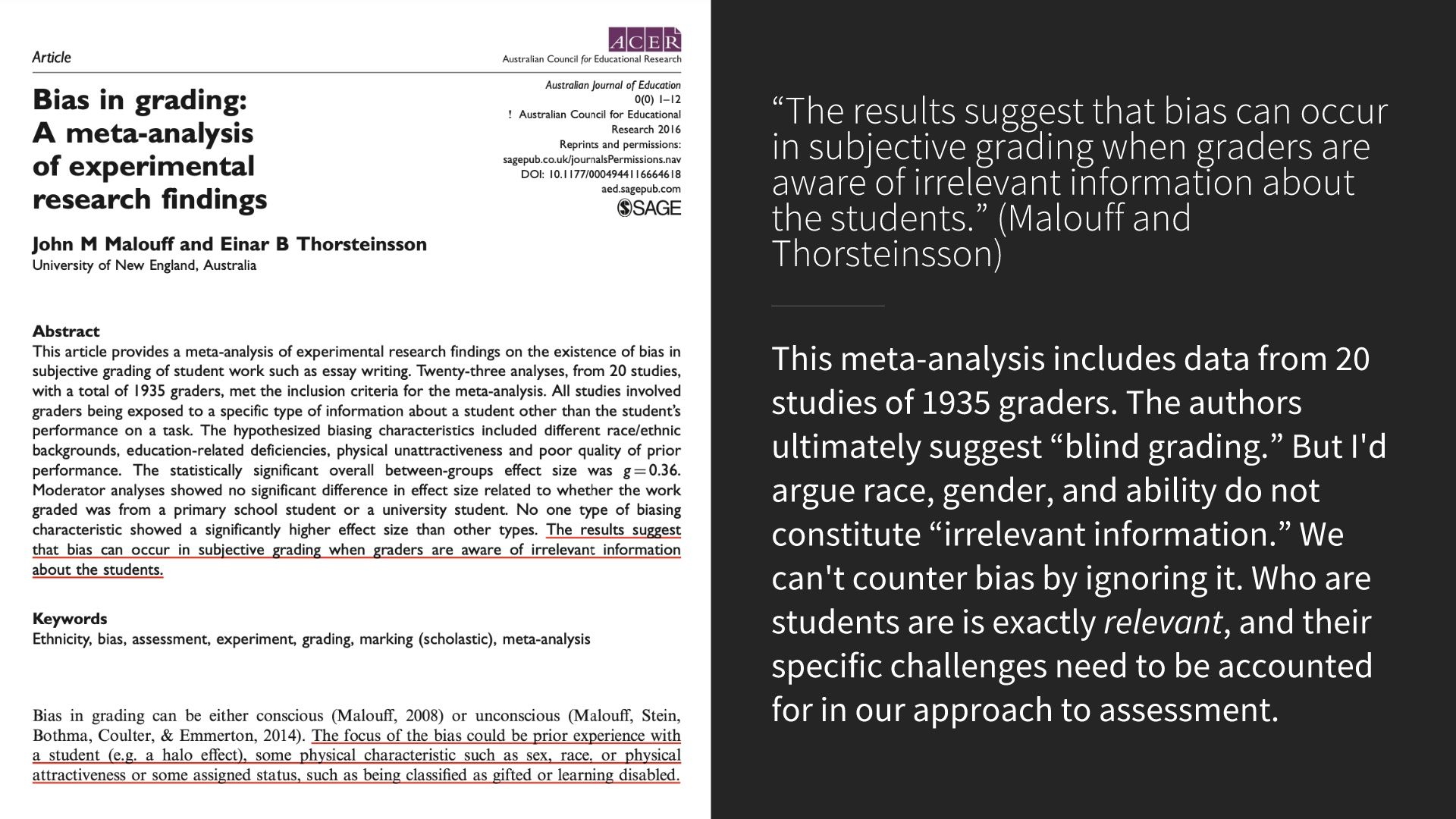

A meta-analysis from Malouff and Thorsteinsson includes data from 20 studies of 1935 graders finds that "bias can occur in subjective grading when graders are aware of irrelevant information about the students." The authors ultimately suggest "blind grading." But I'd argue race, gender, and ability do not constitute "irrelevant information." We can't counter bias by ignoring it. Who our students are is exactly relevant, and their specific challenges need to be accounted for in our approach to assessment.

“Food insecurity is a significant factor in determining the average math-SAT score. An increase in food insecurity lowers the students’ Math-SAT scores.” ~ Sharma and Carr, “Food Insecurity and Standardized Test Scores”

Ozturk, et. al. found that students perform more poorly on exams when they are several weeks removed from receiving food-stamp benefits.

“Children displayed a statistically significant increase in cortisol level in anticipation of high-stakes testing. Large decreases and large increases in cortisol were associated with underperformance on the high-stakes test.” ~ Heissel, et. al., “Testing, Stress, and Performance: How Students Respond Physiologically to High-Stakes Testing”

Grades are anathema to the presumption of the humanity of students, support for their basic needs, and engaging them as full participants in their own education. Invigilated exams won’t ensure integrity. Plagiarism detection tech won’t unseat online paper mills. Incessant surveillance won’t help us listen better for the voices of students asking for help.

Taking grades at least partly off the table means I have a whole different set of conversations with students I work with. My goal isn't to create a learning environment entirely free of grades (they still get graded in other classes), but to create a safe space for students to ask critical questions about grades, about how school works, and about their own learning.

Ungrading starts with teachers just talking to students about grades. Demystifying grades (and the culture around them) gives students a sense of ownership over their own education.

Alternative Forms of Assessment:

- Minimal Grading: Using scales with fewer gradations to make grading “simpler, fairer, clearer” (Elbow)

- Contract Grading: Grading contracts convey expectations about what is required for each potential grade. Students work toward the grade they want to achieve, and goalposts don’t unexpectedly shift.

- Authentic Assessment: Having students write for real-world audiences, focusing on intrinsic motivations, and drawing students into the design of assignments / assessments.

- Process Letters: Asking students to reflect on their work and offer feedback on those reflections. Students help guide the grading of their own work.

The statement about assessment from my own syllabi:

This course will focus on qualitative not quantitative assessment, something we’ll discuss during the class, both with reference to your own work and the works we’re studying. While you will get a final grade at the end of the term, I will not be grading individual assignments, but rather asking questions and making comments that engage your work rather than simply evaluate it. You will also be reflecting carefully on your own work and the work of your peers. The intention here is to help you focus on working in a more organic way, as opposed to working as you think you’re expected to. If this process causes more anxiety than it alleviates, see me at any point to confer about your progress in the course to date. If you are worried about your grade, your best strategy should be to join the discussions, do the reading, and complete the assignments. You should consider this course a “busy-work-free zone.” If an assignment does not feel productive, we can find ways to modify, remix, or repurpose the instructions.

I’ve foregone grades on individual assignments for over 20 years. My goal in questioning grades has been to more honestly engage student work rather than simply evaluate it. This practice continues to feel like an act of personal, professional, and political resistance.

While I've experimented with many alternatives to traditional assessment, I have primarily relied on self-assessment. I turn in final grades for the course, but those grades usually match the grades students have given themselves.

My view of students as complex and deeply committed to their education is fueled by the thousands of self-reflection letters I've read throughout my career. What happens with almost every single student is that any assumption I might make about them is squashed by what they write about themselves and their work.

“We need more, not fewer, ways to listen for the voices of students reflecting on education. We need more, not fewer, ways to include students in conversations about the future of teaching and learning in college. These conversations cannot begin by sending a signal to students that their voices don’t matter.” ~ Sara Goldrick-Rab and Jesse Stommel, “Teaching the Students We Have Not the Students We Wish We Had”

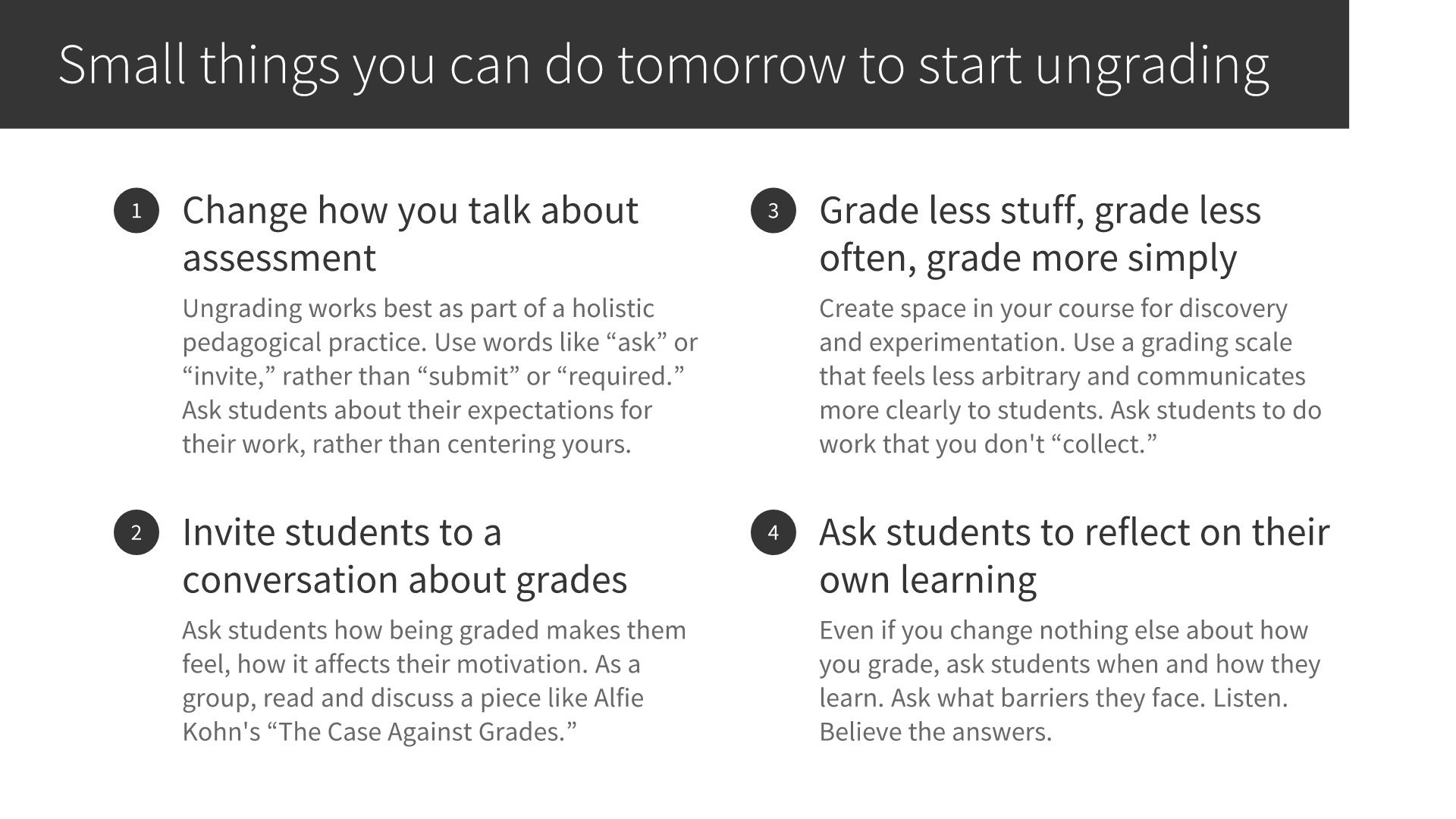

Small things you can do tomorrow to start ungrading:

- Change how you talk about assessment: Ungrading works best as part of a holistic pedagogical practice. Use words like "ask" or "invite," rather than "submit" or "required." Ask students about their expectations for their work, rather than centering yours.

- Invite students to a conversation about grades: Ask students how being graded makes them feel, how it affects their motivation. As a group, read and discuss a piece like Alfie Kohn's "The Case Against Grades."

- Grade less stuff, grade less often, grade more simply: Create space in your course for discovery and experimentation. Use a grading scale that feels less arbitrary and communicates more clearly to students. Ask students to do work that you don't "collect."

- Ask students to reflect on their own learning: Even if you change nothing else about how you grade, ask students when and how they learn. Ask what barriers they face. Listen. Believe the answers.